Exton, PA - September, 2023

1. As someone who began photography very young, what drives your interest in black and white photography? Has your focus always been in black and white? What interests you about a world portrayed in black and white?

My focus has almost always been black-and-white, unless doing travel or nature photography, or journalism, which are very different from this project. There is one color photograph in Blackbird. But there is a reason for it, and I couldn't have done the book without that one color photo.

In the film days color was too hard to print yourself. Today anyone can process color on a computer, but I still prefer black-and-white because it automatically imposes a first layer of separation and abstraction from reality. And with color many more things need to fall into place. When catching strangers unaware, such as we do for this book, something a simple as one person wearing a red shirt can spoil the photo.

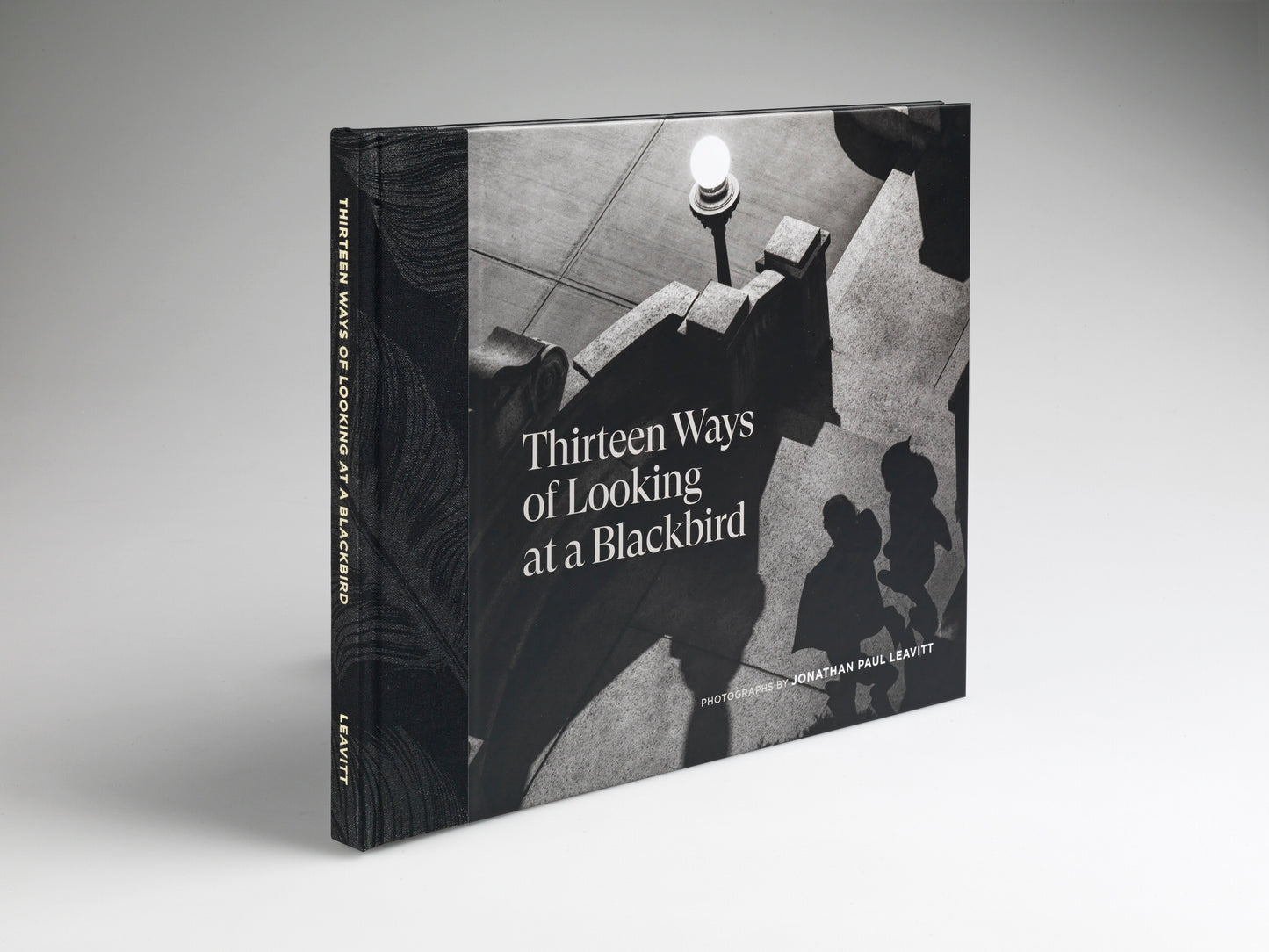

2. What are the themes carried throughout Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird? How did this title arise?

The book is a meditation on the poem of that name by Wallace Stevens, which is a series of thirteen epigrams. Each photo in the book corresponds to a line in the poem. But it is not an illustration of the poem. And there is not a single picture of a blackbird, except for a cameo appearance in the credits.

The photographs represent further thoughts or personal interpretations that occurred to me upon reading the poem. Each line furnishes a brief caption such as "are one" or "the river is flowing". One line in the poem reads "the beauty of innuendos". The corresponding photograph attempts to illustrate what the beauty of innuendos means to me -- a very abstract theme indeed.

3. How were you thinking while you were capturing these images?

When capturing images there is no time to think; it is time to fall back on reflexes. Imagine the scene corresponding to "the beauty of innuendos". A man approaches,

walking a dog. It looks banal: man walks dog. But you watch them to see what they do next, covertly tracking the dog without making them aware of the camera. Then a woman appears from outside the frame and pets the dog. All three heads -- the woman's, the man's, and the dog's -- are outside the frame. You only see their hands and arms interacting. Their existence off-camera is implied. To make that photo your finger had to be on the shutter button already, before the woman appeared. So you need to track many, many apparently meaningless situations to catch one that arranges itself into a poem.

At home, with the luxury of time, you can ask yourself whether you overcame the triteness of "man walks dog" and broke through into some new territory that transcends the unremarkable subject. That is what I look for. Reality is cliché; it is our job to transcend it.

4. Is Blackbird biographical? Autobiographical? Commentary? Other?

It is autobiographical but not in a literal way. I am not telling a particular story about myself or anyone else. But I am trying to show what is feels like to me, to move through the world. Since an early age I was always uninterested in the quotidian aspects of life. No matter how beautiful or attractive, photographs of a beach at dawn, a boy riding a bicycle, a man walking a dog, people riding the subway, are things we have all seen many times before. In the book you will find those things, but I believe we have overcome the triteness and banality of the subjects, and turned each into a meditation on a particular metaphor.

5. How long did this book's contents take to create?

All but two of the photos were shot over a period of four years, from 2019 until practically the day before it went to press. Just before the book went to press I realized, and verified through Facebook, that Plate 10 accidentally depicted a person my wife knows, having an extramarital affair. I had no idea when I took the photo in a public place. So we needed a substitute photo. With that assignment, we went to a jazz club in New York and I came away with the image that now appears in the book. It was taken literally under the table, in almost complete darkness with an F1.0 lens. That's what the combination of Leica glass and sensors can do.

6. What was important that this book "get right", be it a technical aspect, the text, the greyscale, the overall feel, etc. How has Brilliant helped carry your vision along with you?

I really feel that if I had gone to just any other press, the book would not be half as good. I went to Brilliant because more than one famous photographer recommended it, and now I see why. Bob Tursack is more than just a printer; he helps the artists take their work to a higher level, but without ever interfering in the process of making the art. He helped the book be all it can be. I love inky blacks. And more important, the hero of our story, the blackbird, embodies inky blacks. Though the blackbird never actually appears until the credits, rich black tones are what makes B&W photography worth doing, and they are the anchor for all these photos but one. I know nothing about how to achieve this using a Heidelberg press, but Brilliant Graphics really has the capacity to configure and lay down those inks perfectly. They also created a "varnish window" over each photo to deepen the effect still further. The results are as good or better than any photo book I have ever seen.

7. How do you see the art of photography changing today? What do you feel is important to preserve about this form of art?

Sometimes I wonder if the era of poetic metaphors is passing, after perhaps 500 years of glory, and a new era is coming devoted other ideas about art. Photographic images are more available than ever before, but the sheer number of new images makes it hard to sort out the profound from the ordinary or silly. In the 1700s and early 1800s scarcely anyone but the very wealthy had meat to eat; it was only a few times a year, perhaps on Christmas or at a wedding. Today people can eat meat every day; but no one remembers what it tasted like. I hope that with the new universal abundance and availability of photography, people do not forget the "taste" of a great photograph.

8. Is there anything about your story and this book you'd want people to know? Please elaborate if you wish.

1. As someone who began photography very young, what drives your interest in black and white photography? Has your focus always been in black and white? What interests you about a world portrayed in black and white?

My focus has almost always been black-and-white, unless doing travel or nature photography, or journalism, which are very different from this project. There is one color photograph in Blackbird. But there is a reason for it, and I couldn't have done the book without that one color photo.

In the film days color was too hard to print yourself. Today anyone can process color on a computer, but I still prefer black-and-white because it automatically imposes a first layer of separation and abstraction from reality. And with color many more things need to fall into place. When catching strangers unaware, such as we do for this book, something a simple as one person wearing a red shirt can spoil the photo.

2. What are the themes carried throughout Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird? How did this title arise?

The book is a meditation on the poem of that name by Wallace Stevens, which is a series of thirteen epigrams. Each photo in the book corresponds to a line in the poem. But it is not an illustration of the poem. And there is not a single picture of a blackbird, except for a cameo appearance in the credits.

The photographs represent further thoughts or personal interpretations that occurred to me upon reading the poem. Each line furnishes a brief caption such as "are one" or "the river is flowing". One line in the poem reads "the beauty of innuendos". The corresponding photograph attempts to illustrate what the beauty of innuendos means to me -- a very abstract theme indeed.

3. How were you thinking while you were capturing these images?

When capturing images there is no time to think; it is time to fall back on reflexes. Imagine the scene corresponding to "the beauty of innuendos". A man approaches,

walking a dog. It looks banal: man walks dog. But you watch them to see what they do next, covertly tracking the dog without making them aware of the camera. Then a woman appears from outside the frame and pets the dog. All three heads -- the woman's, the man's, and the dog's -- are outside the frame. You only see their hands and arms interacting. Their existence off-camera is implied. To make that photo your finger had to be on the shutter button already, before the woman appeared. So you need to track many, many apparently meaningless situations to catch one that arranges itself into a poem.

At home, with the luxury of time, you can ask yourself whether you overcame the triteness of "man walks dog" and broke through into some new territory that transcends the unremarkable subject. That is what I look for. Reality is cliché; it is our job to transcend it.

4. Is Blackbird biographical? Autobiographical? Commentary? Other?

It is autobiographical but not in a literal way. I am not telling a particular story about myself or anyone else. But I am trying to show what is feels like to me, to move through the world. Since an early age I was always uninterested in the quotidian aspects of life. No matter how beautiful or attractive, photographs of a beach at dawn, a boy riding a bicycle, a man walking a dog, people riding the subway, are things we have all seen many times before. In the book you will find those things, but I believe we have overcome the triteness and banality of the subjects, and turned each into a meditation on a particular metaphor.

5. How long did this book's contents take to create?

All but two of the photos were shot over a period of four years, from 2019 until practically the day before it went to press. Just before the book went to press I realized, and verified through Facebook, that Plate 10 accidentally depicted a person my wife knows, having an extramarital affair. I had no idea when I took the photo in a public place. So we needed a substitute photo. With that assignment, we went to a jazz club in New York and I came away with the image that now appears in the book. It was taken literally under the table, in almost complete darkness with an F1.0 lens. That's what the combination of Leica glass and sensors can do.

6. What was important that this book "get right", be it a technical aspect, the text, the greyscale, the overall feel, etc. How has Brilliant helped carry your vision along with you?

I really feel that if I had gone to just any other press, the book would not be half as good. I went to Brilliant because more than one famous photographer recommended it, and now I see why. Bob Tursack is more than just a printer; he helps the artists take their work to a higher level, but without ever interfering in the process of making the art. He helped the book be all it can be. I love inky blacks. And more important, the hero of our story, the blackbird, embodies inky blacks. Though the blackbird never actually appears until the credits, rich black tones are what makes B&W photography worth doing, and they are the anchor for all these photos but one. I know nothing about how to achieve this using a Heidelberg press, but Brilliant Graphics really has the capacity to configure and lay down those inks perfectly. They also created a "varnish window" over each photo to deepen the effect still further. The results are as good or better than any photo book I have ever seen.

7. How do you see the art of photography changing today? What do you feel is important to preserve about this form of art?

Sometimes I wonder if the era of poetic metaphors is passing, after perhaps 500 years of glory, and a new era is coming devoted other ideas about art. Photographic images are more available than ever before, but the sheer number of new images makes it hard to sort out the profound from the ordinary or silly. In the 1700s and early 1800s scarcely anyone but the very wealthy had meat to eat; it was only a few times a year, perhaps on Christmas or at a wedding. Today people can eat meat every day; but no one remembers what it tasted like. I hope that with the new universal abundance and availability of photography, people do not forget the "taste" of a great photograph.

8. Is there anything about your story and this book you'd want people to know? Please elaborate if you wish.

This book is aimed not only at a photography audience, but also at devotees of Wallace Stevens. I would hope to do for photography what he did for poetry. In an altercation with Robert Frost, Stevens is reported to have said "The trouble with you Robert, is that you write about subjects." I hope people see that this book is not about subject matter; it is an attempt to transcend subject matter.

Brilliant Brilliant…!!!